Experiments attempting to collect evidence that our universe is a 2-D hologram keep re-surfacing. Back in 2014, Fermilab's Craig Hogan designed an experiment to test the theory. Well, he did not find evidence that he was looking for. This article on that experiment is not too long and not too technical, so you may find it curiously refreshing. As the article says, he has not given up and is continuing with his next experiment. I seem to recall that his experiment, which is not much described in the article, was measuring background radiation from the Big Bang. (By the way, I'm baffled by that name as there was no Bang.)

Today scientists from Canada, England and the U.S. report that they have some evidence that revives the 2-D hologram theory of the universe. I, of course, don't understand this stuff, and all I can find is that small abstract of the paper (apart from goofy news reports about it), but it sounds like their "evidence" is more statistical appropriateness of the holographic model compared to the Standard Model.

Maybe this is why we have landed in the realm of alternative facts. Science keeps pushing us to leave "true" in favor of statistically appropriate.

Monday, January 30, 2017

Monday, January 23, 2017

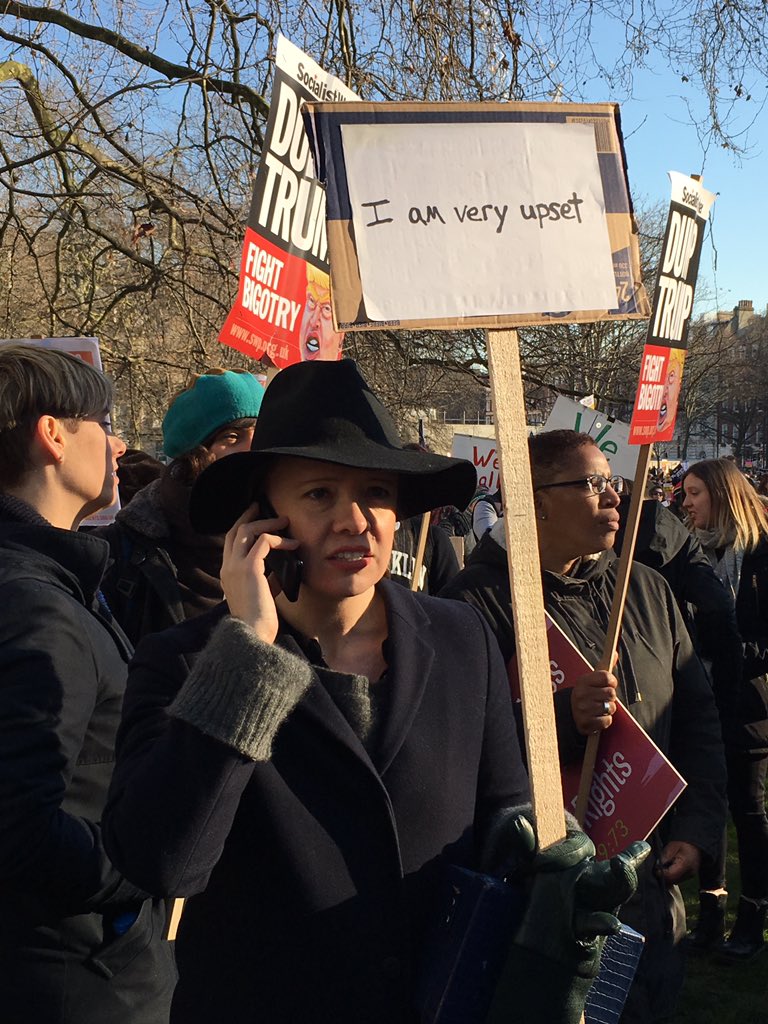

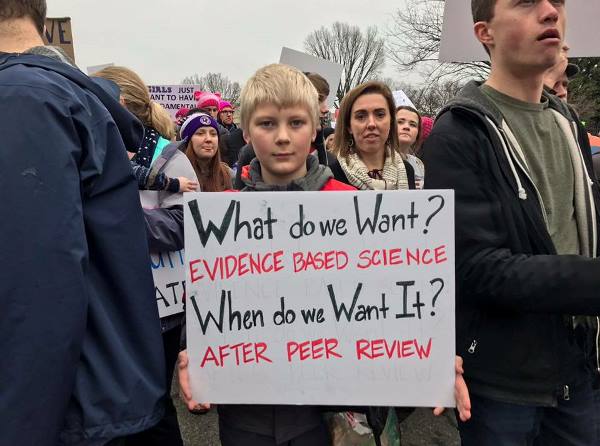

Huge Women's March Addendum

Huge women's march

I watched much of it on the NYT website. Perhaps Renée (Washington), Lisa (Washington), Ellen (New York) and others can help me out, but here are the best signs I saw:

• Fight like a girl

• Make love not wall (Paris, France)

• Resistance is fertile (Kolkata, India)

• Respect existence or expect resistance

• Keep the mitts off the lady bits

• Make America think again (Florence, Italy)

• Don't forget to set your clocks back 300 years

• No hate, no fear, everyone is welcome here (Berlin, Germany)

• Keep calm and smash fascism (Helsinki, Finland)

• Hasta la vista sociedad machista (San Jose, Costa Rica)

• Fight like a girl

• Make love not wall (Paris, France)

• Resistance is fertile (Kolkata, India)

• Respect existence or expect resistance

• Keep the mitts off the lady bits

• Make America think again (Florence, Italy)

• Don't forget to set your clocks back 300 years

• No hate, no fear, everyone is welcome here (Berlin, Germany)

• Keep calm and smash fascism (Helsinki, Finland)

• Hasta la vista sociedad machista (San Jose, Costa Rica)

Saturday, January 14, 2017

Reasons to Look Forward to 2017

Things are looking pretty bleak these days, no? Trump's election, Brexit. the Orlando shooting, the tragedy of Aleppo, global warming, and the collapse of Venezuela. It’s been a rough year. But, before you decide that the world is going to hell in a handcart, think again. On New Years eve, retired Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield laid out a series of tweets identifying 46 positive things that have happened in the last year -- some of them quite spectacular, like halving the number of veterans in the US who are homeless in the past 5 years, with a nearly 20% drop in 2016, or having the fewest per capita deaths in aviation of any year on record, or India planting 50 million trees in a single day. And many of them I knew nothing about. He concludes with "There are countless more examples, big and small. If you refocus on the things that are working, your year will be better than the last." See Looking Up (You'll need to keep hitting the "Show More" button to read them all.)

Hadfield is not the only one looking up these days. Swedish writer Johan Norberg argues in his new book Progress: Ten Reasons to Look Forward to the Future that the doom and gloom forecast is not just incorrect, but is directly the opposite of what is actually happening in the world. See Why 2016 Is Actually the Best Time in All of History to Be Alive; also Better and better. Norberg says that we misperceive what is happening in the globe because of the unrelenting parade of negative news stories promoted in the media -- if it bleeds it leads -- and we have been duped into believing the worst. Norberg says that the problem with advocating that "everything is going downhill" is that this message is exactly what feeds populist politics like Trump and Brexit. The world is in turmoil and we must circle the wagons. I also worry that all this talk of impending catastrophe will discourage people laboring in the field improving the world, since its all pointless, and the doom prediction becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

And, by the way, other remarkable things are happening. As I discussed with Lainie at our New Years Eve gathering, the costs of renewable energy sources are steadily dropping and will soon undercut the cost of fossil fuels. Consequently, as a matter of economics, renewables will end up being the preferred choice. Renewables are already cheaper than coal, and wind energy (with tax credits) narrowly beats out natural gas. There is every reason to believe that the cost of renewables will continue to drop. Trump Can't Stop the Energy Revolution; Fossil fuels are dead – the rest is just detail; Wind and solar energy to be cheaper than fossil fuels by 2018; People are worried Trump will stop climate progress. The numbers suggest he can’t.

Meanwhile, the World Bank has announced that, for the first time in known history, less than 10 percent of the global population now lives in extreme poverty (i.e., earning less than $1.25 a day). According to the The Economist, "Between 1990 and 2010, [the number of people in extreme poverty] fell by half as a share of the total population in developing countries, from 43% to 21%—a reduction of almost 1 billion people. Towards the end of poverty. The UN has targeted 2030 as the year that we eliminate all extreme poverty in the world. Here's the progress so far:

Likewise, the world's children are becoming better educated. We've seen the lowest-ever proportion of kids out of primary school according to the UN—less than one in 10. The number of kids out of school has fallen from 100 million in 2000 to 57 million in 2015. Consequently, literacy is rising. Almost 90% of the world's population can now read:

And finally, if you are worried about overpopulation, fertility rates are dropping. Go forth and multiply a lot less.

More people than ever are being fed around the world. Famine deaths are increasingly rare and the proportion of the world’s population that is undernourished slipped from 19 percent to 11 percent between 1990 and 2015. Add to that the fact that global child mortality from all causes has more than halved since 1990. That means 6.7 million fewer kids under the age of five are dying each year compared to 1990. Worldwide life expectancy is also shooting up:

And finally, if you are worried about overpopulation, fertility rates are dropping. Go forth and multiply a lot less.

From where I stand, the future's looking mighty good.

Friday, January 13, 2017

Practical Benefits of Philosophy - technology edition

A number of years ago Myk presented the “Practical Benefits of Philosophy” in which he compared psychologist Carol Dweck’s ideas about growth and fixed mindsets to the philosophies of existentialism and essentialism. We had some fun (i.e. worthwhile) discussions on the topic (in my humble opinion). In spite of the fact that many family members support the study of philosophy as important to providing practical benefits in life, many others, like much of the world, see philosophy as a waste of time at best, and word manipulation at worst. Well, we all have our predilections and proper experiences. I’d like to give a totally different example of the “Practical Benefits of Philosophy”.

Unfortunately, it involves the world of programming, a world no one who reads this blog has any interest (unless big Dave gets some time off from work and chasing after kids to read).

Apple Corp. created a new, very well received language a few years ago called Swift. It was created by a very intelligent person named Chris Lattner. Mr. Lattner, as a graduate student, designed LLVM (Low Level Virtual Machine), an innovative infrastructure for optimizing compilers. A compiler is code that creates machine code from the code programmers write in. Practically all languages now use Lattner’s LLVM to complie code.

Anyway, he was hired by Apple, did fantastic work with LLVM and other creations which form the core of Apple’s development environment. Then he created the new language Swift. Lattner announced a few days ago he is leaving Apple for a new challenge at Tesla. The person taking over Lattner’s responsibiilties at Apple and head of the Swift language is Ted Kremenek. Lattner admits that for some time now Kremenek has been more or less running the show, so it will be a smooth transition.

Ted Kremenek has a doctorate in Philosophy from Stanford.

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

Word Play Aloud (Sound and Meaning)

"Wind the wrap around the wound to ward off the wind, and it will wind up well." So he wound the wrap around the wound, and it wound up well.

Friday, January 6, 2017

Updating Ericsson, and Whatever Happened to Dan McLaughlin?

Some years ago I posted a few remarks about K. Anders Ericsson, a psychologist at Florida State University: Ericsson Put to the Test and Practical Benefits of Philosophy: 4. The Question. Ericsson caused a bit of a stir when he announced that inborn talent had almost nothing to do with determining one's peak level of performance in just about anything. “The traditional view of talent, which concludes that successful individuals have special innate abilities and basic capacities, is not consistent with the reviewed evidence," he says. Rather, "[t]he differences between expert performers and normal adults are not immutable, that is, due to genetically prescribed talent. Instead, these differences reflect a life-long period of deliberate effort to improve performance."

Ericsson also maintained that not just any kind of effort produces expert performance; rather, you must apply yourself to what Ericsson calls "deliberate practice." Deliberate practice is long-term effort specifically focused on improving your performance, that is, it is designed to "stretch[] yourself beyond what you can currently do,” provides feedback on results from an expert and involves high levels of repetition.

Ericsson then makes the bold claim that 10,000 hours of this sort of deliberate practice will make anyone an expert in any field.

Which brings us to Dan McLaughlin and The Dan Plan. Dan wanted to test Ericsson's proposition. He took an activity that he had never done before -- golf -- and proceeded to vigorously follow Ericsson's deliberate practice strategy. His plan was to log 30-plus hours a week until he hit the magic 10,000 hour milestone by October of 2016. His ultimate goal was to obtain a PGA TOUR card.

In the meantime, other psychologists have challenged Ericsson's theory. Mostly, they argue that the interplay between talent and effort is far more complex than Ericsson asserts. Zach Hambrick worked with Ericsson as a graduate student at Florida State in 1996. He and Ericsson grew close; Hambrick became an admirer. “It was fantastic. Wonderful, inspiring conversations,” Hambrick recalls. So, when Hambrick left Florida State, he continued the research into the effects of practice verses talent.

Only, his research showed that talent not only counted, it counted a lot. Practice still accounted for differences in performance, but innate talent counted more. For example, pianists with better working memory -- a heritable trait -- were better at sight reading, and increased practice did not alter the effect. Other studies, however, have shown that practice and effort can still make a sizable difference, along with talent. Vanderbilt University has been conducting a longitudinal study of students who, at the age of thirteen, scored in the top one per cent of mathematical-reasoning ability. So far, the study has revealed that, while many of the gifted students have excelled in academic accomplishment, patents, publications and organizational leadership, others have ended up with achievements indistinguishable from their less talented 13-year-old peers. It seems that genes set the upper limit of performance, but without practice and effort, you'll never get there. For all the details, see the New Yorker article PRACTICE DOESN’T MAKE PERFECT. And here, Hambrick weighs in by way of a Scientific American article. Is Innate Talent a Myth?

For an answer to Jim's question posed to Ericsson himself about whether the passion to work hard is something inherited or whether it can be developed by effort and resolve, the New Yorker article said this:

If you believe the "Post Mortem" article, Dan's apparent failure was due to his abandonment of the Ericsson deliberate practice regimen. From his blog, however, it looks like Dan was sidelined by chronic back pain and the fact that he was running out of money. In any event, I don't think Ericsson will be citing McLaughlin's experiment in any of his upcoming papers.

Incidentally, as the New Yorker article points out, Ericsson has not budged from his initial thesis, except to concede that inherited traits of body size and height may affect performance. (He has also admitted that starting your deliberate practice late in life may also limit performance.) He told the author of the New Yorker article, “I have no problem conceptually with this idea of genetic differences, but nothing I’ve seen has convinced me this is actually the case. There’s compelling evidence that if it’s length of bones, that cannot be explained by training. We know you can’t influence diameter of bones. But that’s really it.”

One last personal point. There may well be some ultimate genetic barrier for each of us in any given skill, but how relevant is it? There is also probably also some absolute maximum speed human beings as a species can run set by our genes, but the mile record keeps steadily dropping. So, whatever it is, we haven't reached it yet.

My guess is that individuals likewise rarely if ever reach their personal genetic limit that couldn't be improved upon at least somewhat. I used to work with a very fine attorney who said that he had done nothing in his career -- write a brief, deliver an argument, conduct a cross examination, you name it -- that he couldn't have done better. So, it seems to me, that mostly the barriers we encounter are not genetic ones but those that result from a lack of effort and focus. At least, that's how I experience it. Of course, if our willingness to work is genetically determined, we have a built in excuse.

Ericsson also maintained that not just any kind of effort produces expert performance; rather, you must apply yourself to what Ericsson calls "deliberate practice." Deliberate practice is long-term effort specifically focused on improving your performance, that is, it is designed to "stretch[] yourself beyond what you can currently do,” provides feedback on results from an expert and involves high levels of repetition.

Ericsson then makes the bold claim that 10,000 hours of this sort of deliberate practice will make anyone an expert in any field.

Which brings us to Dan McLaughlin and The Dan Plan. Dan wanted to test Ericsson's proposition. He took an activity that he had never done before -- golf -- and proceeded to vigorously follow Ericsson's deliberate practice strategy. His plan was to log 30-plus hours a week until he hit the magic 10,000 hour milestone by October of 2016. His ultimate goal was to obtain a PGA TOUR card.

In the meantime, other psychologists have challenged Ericsson's theory. Mostly, they argue that the interplay between talent and effort is far more complex than Ericsson asserts. Zach Hambrick worked with Ericsson as a graduate student at Florida State in 1996. He and Ericsson grew close; Hambrick became an admirer. “It was fantastic. Wonderful, inspiring conversations,” Hambrick recalls. So, when Hambrick left Florida State, he continued the research into the effects of practice verses talent.

Only, his research showed that talent not only counted, it counted a lot. Practice still accounted for differences in performance, but innate talent counted more. For example, pianists with better working memory -- a heritable trait -- were better at sight reading, and increased practice did not alter the effect. Other studies, however, have shown that practice and effort can still make a sizable difference, along with talent. Vanderbilt University has been conducting a longitudinal study of students who, at the age of thirteen, scored in the top one per cent of mathematical-reasoning ability. So far, the study has revealed that, while many of the gifted students have excelled in academic accomplishment, patents, publications and organizational leadership, others have ended up with achievements indistinguishable from their less talented 13-year-old peers. It seems that genes set the upper limit of performance, but without practice and effort, you'll never get there. For all the details, see the New Yorker article PRACTICE DOESN’T MAKE PERFECT. And here, Hambrick weighs in by way of a Scientific American article. Is Innate Talent a Myth?

For an answer to Jim's question posed to Ericsson himself about whether the passion to work hard is something inherited or whether it can be developed by effort and resolve, the New Yorker article said this:

As it turns out, though, even work ethic may be heritable. Hambrick has recently published a study on the heritability of practice, using eight hundred pairs of twins. “Practice is actually heritable. There have now been two reports of this—ours, and one using ten thousand twins. And practice is substantially heritable.”So, that leaves the question, whatever happened to Dan McLaughlin? That, I discovered is a bit of a mystery. Initially, I found no internet news articles whatsoever on Dan's progress to date. So, I decided to go directly to his website, The Dan Plan. Ominously, his blog ends abruptly on November 23, 2015. No less mysteriously, Dan's "Countdown to 10,000!" page ends without warning or explanation at the week of April 27 to May 2, 2015. The Dan Plan Countdown. And then, after much searching, I found this obscure article, Post Mortem on the Dan Plan, that said that Dan has abandoned the plan and moved on to selling artisanal sodas in Portland, Oregon. I wasn't sure about the reliability of this website, but I tracked down another article about the soda company where Dan is supposed to be working and, sure enough, his name and picture are right there. Bubble Rap: Talking Artisanal Soda with Portland Soda Works.

If you believe the "Post Mortem" article, Dan's apparent failure was due to his abandonment of the Ericsson deliberate practice regimen. From his blog, however, it looks like Dan was sidelined by chronic back pain and the fact that he was running out of money. In any event, I don't think Ericsson will be citing McLaughlin's experiment in any of his upcoming papers.

Incidentally, as the New Yorker article points out, Ericsson has not budged from his initial thesis, except to concede that inherited traits of body size and height may affect performance. (He has also admitted that starting your deliberate practice late in life may also limit performance.) He told the author of the New Yorker article, “I have no problem conceptually with this idea of genetic differences, but nothing I’ve seen has convinced me this is actually the case. There’s compelling evidence that if it’s length of bones, that cannot be explained by training. We know you can’t influence diameter of bones. But that’s really it.”

One last personal point. There may well be some ultimate genetic barrier for each of us in any given skill, but how relevant is it? There is also probably also some absolute maximum speed human beings as a species can run set by our genes, but the mile record keeps steadily dropping. So, whatever it is, we haven't reached it yet.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6513771/ourworldindata_life-expectancy-by-world-region-since-1770-1.png)