Peter Abelard (and Heloise) – Part I

In the last entry in my Theories of Atonement series, I promised to tell you about Peter Abelard’s view of atonement. In preparing that post, however, I kept running across a story that was at least as compelling as any theory of atonement and certainly more dramatic: Abelard’s tragic romance with the extraordinary Heloise d’Argenteuil. The constant intrusions of this history into my research and its unusual power led me to decide to take an unprecedented break from our theoretical discussions and include the story in the series. For those of you who were hoping for the next theory of atonement, I can at least offer you the assurance that I hope to soon post on Abelard’s theory.

1. Introducing Abelard.

Peter Abelard (1079-1142) was the whiz kid of medieval Europe. He is generally acknowledged to be the pre-eminent philosopher and theologian of the twelfth century and the greatest logician of the Middle Ages. If that weren’t enough, he was also a well-respected poet and music composer. In many ways, he was far ahead of his time, anticipating the development of modern thought. Rather than looking to authority for answers, he believed in applying reason: “The first key to wisdom is the constant and frequent questioning. … For it is by doubting that we come to investigate, and by investigating that we recognize the truth.”

He was insightful, witty, charming and an innovative thinker. It is said that he never lost a debate. His principal failing was that he was smart enough to be well aware of his own talents. Consequently, he could be scornful of lesser lights, and loved to humiliate his opponents. His vast intellect and nimble wit drew a generation of Europe's finest minds to Paris to learn from him. Among his students were several future heads of state and three popes. But his arrogance and disagreeable way of treating others earned him plenty of enemies.

2. Peter Abelard and Heloise d'Argenteuil.

|

| Peter Abelard |

2. Peter Abelard and Heloise d'Argenteuil.

Abelard grew up in Brittany, the son of a minor noble. He opted out of the usual career path of the wellborn leading to knighthood and, instead, pursued learning and philosophy. He left Brittany to study in Paris, where he met the lovely Heloise.

Heloise grew up – perhaps an orphan – at the convent of St. Marie in Argenteuil, a Benedictine community near Paris. Apparently, she received a good education there, since Abelard reports that Heloise knew Greek, Hebrew and Latin, a rare achievement for anyone at that time, let alone a woman. Peter the Venerable, the abbot of Cluny (who appears later in this story), once wrote that in wisdom she has “completely excelled all women, and surpassed almost all men.”

|

| Heloise d'Argenteuil |

The best guess is that Abelard and Heloise met around 1115. She was one of his students and in her early to middle twenties (although some historians place her in her late teens). Abelard, already established as a noted philosopher, was in his mid-30’s.

There was in Paris a young creature (ah, Philintus!) formed in a prodigality of nature to show mankind a finished composition; dear Heloise, the reputed niece of one Fulbert, a canon [cleric attached to a cathedral]. Her wit and her beauty would have stirred the dullest and most insensible heart, and her education was equally admirable. Heloise was the mistress of the most polite arts. You may easily imagine that this did not a little help to captivate me; I saw her, I loved her, I resolved to make her love me.

Abelard approached her uncle and offered to tutor Heloise. Beyond Abelard’s wildest dreams, Fulbert not only agreed but offered Abelard room and board as payment for his services. Writes Abelard in the same letter to Philintus, “and can you believe it…he allowed me the privilege of his table, and an apartment in his house?”

Almost immediately, the lessons turned into lovers’ trysts. As Abelard himself admits, there was “more kissing than teaching.” Their passion was tumultuous and intense. Again, from Abelard’s letter to Philintus: “In short, our desires left no stage of love-making untried, and if love could devise something new, we welcomed it. We entered on each joy the more eagerly for our previous inexperience, and were the less easily sated.”

After several months, Fulbert discovered their relationship, and immediately sent Abelard away. The couple continued to meet in secret and a short time later Heloise became pregnant. Abelard decided to take Heloise away from Paris to give birth to her child. As Abelard writes: “Without losing much time in debating, I made her presently quit the Canon's [Fulbert’s] house and at break of day depart for Brittany; where she, like another goddess, gave the world another Apollo, which my sister take care of.” Heloise gave her son the name Astrolabe, an unusual name even in the 12th century. As Abelard tells us, his sister ended up raising the child.

Abelard now had a dilemma. He felt that, to appease Fulbert’s sense of honor, he must marry Heloise. At the same time, a marriage would ruin his career as an academic since the church-run academy took a dim view of matrimony. He therefore proposed to the uncle that he marry Heloise on the condition that Fulbert keep their marriage secret. Heloise initially refused to go along with this plan, believing that the truth would inevitably come to light, and their marriage would then “rob the Church of so shining a light.” She offered to remain his mistress, however, because – interestingly enough – that relationship would not hinder his advancement in the Church. Ultimately, they were married in secret as Abelard had proposed, living separately for public appearance. Heloise returned to live with her uncle.

|

|

Abelard and His Pupil Heloise, Edmund Blair Leighton 1882

|

Abelard now had a dilemma. He felt that, to appease Fulbert’s sense of honor, he must marry Heloise. At the same time, a marriage would ruin his career as an academic since the church-run academy took a dim view of matrimony. He therefore proposed to the uncle that he marry Heloise on the condition that Fulbert keep their marriage secret. Heloise initially refused to go along with this plan, believing that the truth would inevitably come to light, and their marriage would then “rob the Church of so shining a light.” She offered to remain his mistress, however, because – interestingly enough – that relationship would not hinder his advancement in the Church. Ultimately, they were married in secret as Abelard had proposed, living separately for public appearance. Heloise returned to live with her uncle.

This arrangement, however, did not satisfy her uncle and Fulbert began to spread the news of the marriage. Heloise responded by publicly denying the marriage. This infuriated Fulbert and, according to Abelard, he became abusive toward his niece. Fearing for her safety, Abelard removed her from her uncle’s home to the same convent at Argenteuil where she had grown up, there to live there as a lay guest.

This decision proved an extremely unfortunate one for Abelard. In Abelard’s words, “her uncle and his friends and relatives imagined that I had tricked them, and had found an easy way of ridding myself of Heloise by making her a nun.” So, to punish Abelard, a group of Fulbert's friends broke into Abelard's room one night and in an act of extreme barbarity castrated him.

Abelard survived the attack, but his sense of shame was overwhelming. It drove him into monastic life and he joined the cloister at St. Denis in Paris. Abelard insisted that Heloise also take the veil, apparently for no other reason but to ensure that no other man might enjoy her attentions. Heloise, racked with guilt, agreed to Abelard’s request and joined the Argenteuil convent.

The two now led separate lives. The ever-difficult Abelard was expelled twice from the St. Denis monastery. Following his second dismissal, he obtained permission and was given land to found an oratory – a place of private prayer – in Champagne near Troyes. Abelard says that his poverty, however, forced him to resume teaching. When word got out, his former students flocked to the oratory to hear him. As one disapproving church cleric, Roscelin of Compiègne, put it, Abelard once more “gathered his horde of barbarians about him.” To accommodate the students, the “thatch and straw” oratory was expanded and rebuilt of stone and timber.

If there was ever a time of happiness for Abelard since his terrible trauma, this was it. As Abelard said of the oratory, “I had sought refuge there when I was in despair” and “by the Grace of divine consolation found a little peace again.” Indeed, Otto von Freising, a German cleric and later historian who was also studying in Paris at the time, remarked that Abelard, having returned to teaching, had become “more subtle and more learned than ever.” Abelard named the oratory the Paraclete, his place of comfort.

Meanwhile, Heloise rose in the ranks of her order and became the prioress of the abbey at Argenteuil. But, she had her own troubles. She and her nuns were evicted from the abbey by Abelard’s own former community, the monks at St. Denis, claiming ownership of the land. At about the same time, Abelard accepted a position as the abbot at the Abbey of St. Gildas on the coast of Brittany near his family home. He arranged for the nuns of Argenteuil Abbey to take over the Paraclete, where Heloise became the abbess.

|

| Abelard and Heloise from a 14th century manuscript |

3. The Letters

After some 17 years of mostly silence, Abelard and Heloise begin a correspondence while he was at St. Gildas and she was at the Paraclete. She was now about 40, and Abelard was in his early 50’s.

The correspondence actually began with Abelard’s letter to his friend, Philintus, as we mentioned earlier. The letter was an attempt to console a despondent Philintus by telling him of Abelard’s own misfortunes. As Abelard says, “hear but the story of my misfortunes, and yours, Philintus, will be nothing….” Somehow, with no explanation, Heloise obtained the letter. Heloise says only, “A consolatory letter of yours to a friend happened some days since to fall into my hands.”

Heloise was very much affected by Abelard’s account of their affair and his long suffering. Straight away she wrote to him, which began an eloquent and intimate correspondence that now has fixed them in the firmament as two of history’s most famous lovers.

There are unaccounted for discrepancies in both the number of letters and their contents. Some authorities say that there are five personal letters. Other sources say that there are seven letters: four are personal and three are “letters of instruction” containing advice from Abelard in response to Heloise’s questions about religion and religious community. The seven-letter collection also differs in language and contents from the five-letter collection. I have discovered not a hint of explanation for these differences, although I suspect that they are the result of multiple translations of these letters over the years.

I have decided to follow the five-letter collection, mostly because it was more accessible and shorter. Feel free to study the seven-letter collection.

After Abelard’s initial letter to his friend Philintus, Heloise in her response grabs the literary spotlight. What will strike even the most insensitive of readers about her letters is their outpouring of what writer Cristina Nehring calls Heloise’s “rash, ringing, reckless and altogether impious declarations of love” for Abelard.

As she makes clear in her first letter, after almost two decades, her love for Abelard still burns fiercely

As she makes clear in her first letter, after almost two decades, her love for Abelard still burns fiercely

This was my cruel uncle's notions [in castrating Abelard]; he measured my virtue by the frailty of my sex, and thought it was the man, and not the person, I loved. But he has been guilty to no purpose. I love you more than ever; and to revenge myself of him, I will still love you with all the tenderness of my soul till the last moment of my life. If formerly my affection for you was not so pure, if in those days, the mind and the body shared in the pleasure of loving you, I often told you, even then, that I was more pleased with possessing your heart than with any other happiness, and the man was the thing I least valued in you.

The pleasures of lovers that we cultivated together were too sweet to displease me, and can scarcely fade from my memory. Wherever I turn they are always there before my eyes, bringing with them reawakened desires. Not even when I sleep am I spared these illusions. Even during the celebration of the Mass, when our prayers should be purer, lewd fantasies of those pleasures take such a hold upon my unhappy soul that I think more on these turpitudes than on my prayers.

I should be groaning over the sins I have committed, but I can only sigh for what I have lost. Everything we did and also the times and places are stamped on my heart along with your image, so that I live through it all again with you.

Indeed, she sees herself as an unrepentant sinner living among the righteous:

The unhappy consequences of our love and your disgrace have made me put on the habit of chastity, but I am not penitent of the past. Thus I strive and labor in vain. Among those who are wedded to God I am wedded to a man; among the heroic supporters of the Cross I am the slave of a human desire; at the head of a religious community I am devoted to Abelard alone. …. I am, I confess, a sinner, but one who, far from weeping for her sins, weeps only for her lover; far from abhorring her crimes, longs only to add to them; and who, with a weakness unbecoming my state, please myself continually with the remembrance of past delights when it is impossible to renew them.

Elsewhere she adds that "God is my witness that if Augustus, emperor of the whole world, thought fit to honor me with marriage and conferred all the earth on me to possess for ever, it would be dearer and more honorable to me to be called not his empress but your whore."

She is most interesting, however, when she discusses marriage. She argues at one point to Abelard that, though she opposed marrying him, it was not because she did not love him, but because as his mistress she remained free:

You cannot but be entirely persuaded of this by the extreme unwillingness I showed to marry you, though I knew that the name of wife was honourable in the world and holy in religion; yet the name of your mistress had greater charms because it was more free. The bonds of matrimony, however honourable, still bear with them a necessary engagement, and I was very unwilling to be necessitated to love always a man who would perhaps not always love me. I despised the name of wife that I might live happy with that of mistress. …

She stresses that true love is not an attraction to the lover’s wealth or station, but to the man himself: "Riches and pomp are not the charm of love. True tenderness makes us separate the lover from all that is external to him, and setting aside his position, fortune or employments, consider him merely as himself."

Marriage, however, seems to be based upon a women’s love of a man’s possessions:

It is not love, but the desire of riches and position that makes a woman run into the embraces of an indolent husband. Ambition, and not affection, forms such marriages. I believe indeed they may be followed with some honors and advantages, but I can never think that this is the way to experience the pleasures of affectionate union, nor to feel those subtle and charming joys when hearts long parted are at last united. These martyrs of marriage pine always for larger fortunes which they think they have missed. The wife sees husbands richer than her own, and the husband wives better portioned than his. Their mercenary vows occasion regret, and regret produces hatred. Soon they part – or else desire to. This restless and tormenting passion for gold punishes them for aiming at other advantages by love than love itself.

And so, she considers marriage simply a sophisticated form of prostitution:

Nor should she deem herself other than venal who weds a rich man rather than a poor, and desires more things in her husband than himself. Assuredly, whomsoever this concupiscence leads into marriage deserves payment rather than affection; for it is evident that she goes after his wealth and not the man, and is willing to prostitute herself, if she can, to a richer.

Finally, this is her prescription for happiness in the vale of tears here on earth:

If there is anything that may properly be called happiness here below, I am persuaded it is the union of two persons who love each other with perfect liberty, who are united by a secret inclination, and satisfied with each other's merits. Their hearts are full and leave no vacancy for any other passion; they enjoy perpetual tranquility because they enjoy content.

As Cristina Nehring writes, “Here is a voice that refuses to stay in the Middle Ages; it reaches through the centuries and catches us at the throat.”

Abelard’s response is both more conventional and more pious, to the point of exasperation. Unlike Heloise, he now views their love as contemptible: “My love which entangled both of us in sin, deserves not the name of love, for it was naught but carnal lust.” He thinks now of their passion only as the snare of the devil – from which they must escape.

Yet, he is haunted by her memory and cannot rid himself of it.

I had wished to find in philosophy and religion a remedy for my disgrace; I searched out an asylum to secure me from love. I was come to the sad experiment of making vows to harden my heart. But what have I gained by this? If my passion has been put under a restraint my thoughts yet run free. I promise myself that I will forget you, and yet cannot think of it without loving you. My love is not at all lessened by those reflections I make in order to free myself.

Even her long absence has not helped:

We commonly die to the affections of those we see no more, and they to ours; absence is the tomb of love. But to me absence is an unquiet remembrance of what I once loved which continually torments me. I flattered myself that when I should see you no more you would rest in my memory without troubling my mind; that Brittany and the sea would suggest other thoughts; that my fasts and studies would by degrees delete you from my heart. But in spite of severe fasts and redoubled studies, in spite of the distance of three hundred miles which separates us, your image, as you describe yourself in your veil, appears to me and confounds all my resolutions.

And, he still laments his privation: “Oh, what a loss I have sustained when I consider your constancy! What pleasures I have missed enjoying!”

He, nevertheless, insists that they must repent of their love for the sake of their own souls, and must put aside all thoughts of the other. With bitter sarcasm, he tells Heloise that to continue to solicit his love would make her the essentially the devil’s accomplice:

Come, if you think fit, and in your holy habit thrust yourself between God and me and be a wall of separation! Come, and force from me those sighs, thoughts, and vows, which I owe to him only. Assist the evil spirits, and be the instrument of their malice. What cannot you induce a heart to, whose weakness you so perfectly know?

His only salvation lies in her departure from his life: “But rather withdraw yourself, and contribute to my salvation. Suffer me to avoid destruction, I entreat you, by our former tenderest affection, and by our common misfortune. It will always be the highest love to show none…. How happy shall I be if I thus lose you.”

If it weren’t already clear, he adds,

But to forget Heloise, to see her no more, is what Heaven demands of Abelard; and to expect nothing from Abelard, to lose him even in idea, is what Heaven enjoins Heloise. To forget in the case of love is the most necessary penitence, and the most difficult. … The only way to return to God is, by neglecting the creature which we have adored, and adoring God whom we have neglected. This may appear harsh, but it must be done if we would be saved.

Here is the writing of a severely shamed and lacerated man who, after decades, still can find no healing.

Heloise’s response to this letter is even more painful and pitiable to read. Here is how she begins:

I see your heart has deserted me, and you have made greater advances in the way of devotion than I could wish. Alas! I am too weak to follow you; condescend at least to stay for me, and animate me with your advice. Will you have the cruelty to abandon me? The fear of this stabs my heart…. Cruel Abelard! you ought to have stopped my tears, and you make them flow; you ought to have quieted the disorder of my heart, and you throw me into despair.

She goes on to lament that she had forsaken all the delights of the world save one – her thought of Abelard – and even this has been taken from her:

I have renounced without difficulty all the charms of life, preserving only my love, and the secret pleasure of thinking incessantly of you, and hearing that you live. And yet, alas! you do not live for me, and dare not flatter myself even with the hope that I shall ever see you again. This is the greatest of my afflictions.

Merciless Fortune! hadst thou not persecuted me enough? Thou dost not give me any respite; thou hast exhausted all thy vengeance upon me, and reserved thyself nothing whereby thou mayst appear terrible to others.

But ultimately she cannot renounce Abelard:

There are several degrees in glory, and I am not ambitious of the highest; I leave them to those of greater courage who have often been victorious. I seek not to conquer for fear I should be overcome; happiness enough for me to escape shipwreck and at last reach port. Heaven commands me to renounce my fatal passion for you, but oh! my heart will never be able to consent to it. Adieu.

Abelard does not respond to this letter, and Heloise writes to him again. She begins by chiding him for not writing. But then announces that finally, she is free of his memory and resolves to disengage from him:

At last, Abelard, you have lost Heloise forever. Notwithstanding all the oaths I made to think of nothing but you, and to be entertained by nothing but you, I have banished you from my thoughts, I have forgot you. Thou charming idea of a lover I once adored, thou wilt be no more my happiness! Dear image of Abelard! thou wilt no longer follow me, no longer shall I remember thee.

No sooner does she declare that she has banished Abelard from her thoughts than she disavows her resolve:

But what secret trouble rises in my soul—what unthought-of emotion now rises to oppose the resolution I have formed to sigh no more for Abelard? Just Heaven! have I not triumphed over my love? Unhappy Heloise! as long as thou drawest a breath it is decreed thou must love Abelard.

And later she asks if she will ever see him again:

My dear Husband (for the last time I use that title!), shall I never see you again? Shall I never have the pleasure of embracing you before death? What dost thou say, wretched Heloise? Dost thou know what thou desirest? Couldst thou behold those brilliant eyes without recalling the tender glances which have been so fatal to thee? Couldst thou see that majestic air of Abelard without being jealous of everyone who beholds so attractive a man? That mouth cannot be looked upon without desire; in short, no woman can view the person of Abelard without danger.

And she ends her letter by admitting her passion for him and asking for his pity:

I begin to perceive, Abelard, that I take too much pleasure in writing to you; I ought to burn this letter. It shows that I still feel a deep passion for you, though at the beginning I tried to persuade you to the contrary. I am sensible of waves both of grace and passion, and by turns yield to each. Have pity, Abelard, on the condition to which you have brought me, and make in some measure my last days as peaceful as my first have been uneasy and disturbed.

Now, Abelard has suffered enough, and he begins the last letter saying that their correspondence must stop:

Write no more to me, Heloise, write no more to me; 'tis time to end communications which make our penances of nought avail. We retired from the world to purify ourselves, and, by a conduct directly contrary to Christian morality, we became odious to Jesus Christ. Let us no more deceive ourselves with remembrance of our past pleasures; we but make our lives troubled and spoil the sweets of solitude. Let us make good use of our austerities and no longer preserve the memories of our crimes amongst the severities of penance. Let a mortification of body and mind, a strict fasting, continual solitude, profound and holy meditations, and a sincere love of God succeed our former irregularities.

And while they continued to write about religious matters – the origin and role of nuns in the church, Abelard’s proposed rule for the nuns at the Paraclete and his discussion of difficult passages of scripture – the tenor of the letters changed, and they never again wrote of their love or any other personal matters.

It’s no wonder that these letters inspired Alexander Pope’s famous lines in his poem, “Eloisa to Abelard,” and of late made popular by Hollywood:

How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot!

The world forgetting, by the world forgot.

Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind!

Each pray’r accepted, and each wish resign’d

4. The End of It

Love stories tend to be tragic but often end with a sense of promise. And, there is some comfort offered at the conclusion of Heloise and Abelard’s story.

Abelard in his life was twice accused of heresy. In both cases, his charges were heard before local church councils, which are formally convened assemblies of bishops and other dignitaries or theological experts for the purpose of discussing and regulating matters of church doctrine and discipline. They differ from Ecumenical Councils in that they are not world-wide.

The first charges against Abelard were heard by the Council of Soissons in 1121. Pupils of one of Abelard’s opponents charged him with heresy in his teaching on the Trinity. While the record is insufficient to determine what actually took place at the Council, it is clear that Abelard was never formally condemned. He was ordered to recite the Athanasian Creed, and to burn his book on the Trinity but, otherwise, he received no punishment.

The second and more serious set of heresy charges were brought by the powerful Bernard of Clairvaux, none other than the namesake for our own local church back in Mt. Lebanon. Bernard, the hardline defender of orthodoxy – described as “a man whose virtues are easier to admire than they can have been to live with” – accused Abelard of 19 separate heresies. The charges were scheduled to be heard before the Council of Sens in either 1140 or 1141 (historians differ). Bernard, well aware of Abelard’s eloquence and talent for verbal combat, concluded that defeating Abelard in an open debate before the council would be difficult. So, he decided to front-load the legal process. The night before the council convened, Bernard arranged a private meeting of the attending bishops and secured their support against Abelard.

|

| Bernard of Clairvaux |

The next day there were no proceedings. After the charges were read, Abelard refused to respond and announced that he would take his case directly to Pope Innocent II. He and his supporters then walked out of the council. A witness at the council said that Abelard seemed confused and irrational. Historians suggest that it is just as likely that Abelard saw that the fix was in and decided upon the direct papal appeal as a way to avoid the council’s inevitable condemnation. Abelard had some reason to hope for this appeal since he knew the pope, having met with him about the transfer of the Paraclete to Heloise and her nuns. The popes response had been positive and he went so far as to issue a charter placing Heloise’s community under papal protection.

So, Abelard, now in his sixties, set off for Rome. After he departed, the Sens council did indeed condemn him for heresy. Yet, Bernard remained concerned about Abelard’s personal appeal to the pope. In an effort to pre-empt the appeal, Bernard, joined by the council bishops, wrote to the pope, adding accusations against Abelard and cautioning the pope against being taken in by Abelard’s clever-sounding arguments. Bernard’s secretary was dispatched to deliver the letters to Innocent and his curia.

Abelard never made it to Rome. On his way he stopped off, probably to rest, at the great Benedictine monastery of Cluny in Burgundy, where Peter the Venerable (1092-1156) was abbot. While Abelard was at Cluny the written decree of Innocent II confirming the sentence of the Council of Sens reached him. On 16 July 1141, Pope Innocent II issued a bull excommunicating Abelard and his followers and imposing perpetual silence on him, and in a second document he ordered Abelard to be confined in a monastery and his books to be burned.

Peter the Venerable, who recognized Abelard’s brilliance and had no great love of Bernard (Peter in a letter to Bernard once described Bernard's order -- the Cistercians -- as a "new race of Pharisees brought back to the world, dividing themselves from others, preferring themselves to all the rest"), now took up Abelard’s case. He was able to arrange meetings between Abelard and Bernard and achieved a reconciliation between the two. He then wrote to Rome and, based on the reconciliation, obtained a mitigation of Abelard’s sentence. And, as a final kindness, he invited Abelard to stay at Cluny.

So, Abelard remained under the protection of Peter the Venerable at Cluny. As his health gradually deteriorated – historians suspect cancer – he was moved to the small priory at nearby St. Marcel, for its more moderate climate. Abelard died there on 21 April 1142.

|

| Peter the Venerable |

So, Abelard remained under the protection of Peter the Venerable at Cluny. As his health gradually deteriorated – historians suspect cancer – he was moved to the small priory at nearby St. Marcel, for its more moderate climate. Abelard died there on 21 April 1142.

Peter the Venerable informed Heloise of Abelard’s death in a remarkably kind and affectionate letter. He says that, even though he has not had the honor of meeting Heloise:

We were allowed the presence, though, of someone dear to you—I mean the man whose name I must speak often and always with honor, Christ’s servant and true philosopher, Master Peter, whom providence brought to Cluny in the last years of his life and enriched it with his presence “far above gold and topaz.” No brief account can do justice to the holiness, the humility, and the devotion of his life among us—all Cluny is its witness.

He tells Heloise that Abelard maintained his full faculties up until his death:

[At the St. Marcel priory] he renewed his old studies, at least so far as his health would permit, always bending over his books, never letting a moment go by without “either praying or reading or writing or composing,” as was said of Gregory the Great.

And that is where the good angel came upon him, in the midst of his holy work; and he found him, not asleep, as are so many, but alert and wide awake.

Peter concludes by with these words of comfort:

And so, my revered, my dearest sister in the Lord, this man, to whom you clung after your marriage in the flesh with the stronger, finer bonds of divine love, your partner and your guide throughout your long service to God, God now enfolds in His embrace in place of you, as another you, and He keeps him there for you until the coming of the Lord, and the voice of the archangel, and the trumpet blast that signals the descent of God from heaven, when through grace he will be restored to you again.

Although Abelard had been initially buried St Marcel’s, Peter had his remains removed and transferred to the Paraclete and the keeping of Heloise, as Abelard had requested. Peter also granted Abelard a formal absolution which was placed inside his tomb: "I, Peter, abbot of Cluny, who received Peter Abelard as a monk of Cluny, and secretly delivered his body to abbess Heloise and the nuns of the Paraclete, absolve him of all his sins by the authority of almighty God and the support of all the saints. Amen."

Apparently, the intention here was to prevent the rise of old accusations of heresy and the consequent desecration of the grave.

Twenty-two years later, in 1163 or 1164, Heloise was laid to rest at his side. But this was not before in her hands the Paraclete grew to be one of the most distinguished houses in France. She founded six daughter houses in the area of Paris. Papal letters confirm some 29 substantial gifts to her monasteries including “fields, vineyards, meadows, woods, mills, waters, tithes and other things.”

The initial inscription placed over the tomb, written by Peter the Venerable at Abelard’s death, ran:

The Socrates of the Gauls, the greatest Plato of the West, our Aristotle, Peer or superior to all other logicians, whoever they may be, Acknowledged prince of worldly studies, subtle, sharp, and diverse in the range of his talents, Best of all in the force of reason and the art of speaking was Abelard. But with far greater distinction as a professed monk of Cluny, He passed over to the philosophy of Christ. Through his long striving, At the end of his life, he won hope of a place with God’s philosophers.

After Heloise’s death a further inscription was added: “Here, under the same tombstone lies the founder of this monastery, Peter Abelard with Heloise, its first abbess, once joined together in learning, genius, and love, ill-fated marriage and penitence. Now, we hope, united in everlasting joy.”

According to Curiosities of Literature by Isaac Disraeli, “An ancient chronicle of Tours records that when they deposited the body of the Abbess Eloisa [Heloise] in the tomb of her lover, Peter Abelard, who had been there interred twenty years, this faithful husband raised his arms, stretched them, and closely embraced his beloved Eloisa.” Disraeli goes on to say that “it is strange that [André] Du Chesne, the father of French history, not only relates this legendary tale of the ancient chroniclers, but gives it as an incident well authenticated, and maintains its possibility by various other examples.”

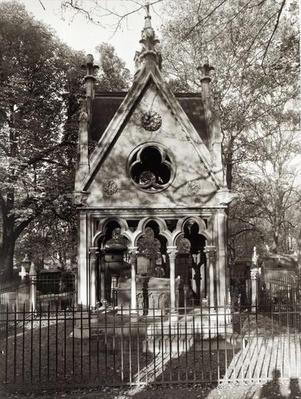

So, in death the two lovers were finally reunited. Their tomb remained at the Paraclete until the French Revolution when the abbey was destroyed and taken over by insurgents. The tomb, however, was preserved and, in 1817, at the request of Empress Josephine, the couple’s remains were transferred to Napoleon’s newly established Père Lachaise Cemetery outside of Paris. They remain there until this day (although lingering doubts remain as to whether the remains in the tomb belong to Heloise and Abelard – seven centuries are a long time to keep things straight).

Since that time, wounded lovers from France and across the world have made pilgrimages to their tomb seeking comfort. Here is Mark Twain’s observation recorded in The Innocents Abroad in 1869.

|

| The Tomb of Abelard and Heloise in Père Lachaise Cemetery |

Since that time, wounded lovers from France and across the world have made pilgrimages to their tomb seeking comfort. Here is Mark Twain’s observation recorded in The Innocents Abroad in 1869.

But among the thousands and thousands of tombs in Père la Chaise, there is one that no man, no woman, no youth of either sex, ever passes by without stopping to examine. … This is the grave of Abelard and Heloise — a grave which has been more revered, more widely known, more written and sung about and wept over, for seven hundred years, than any other in Christendom save only that of the Savior. All visitors linger pensively about it; all young people capture and carry away keepsakes and mementoes of it; all Parisian youths and maidens who are disappointed in love come there to bail out when they are full of tears; yea, many stricken lovers make pilgrimages to this shrine from distant provinces to weep and wail and “grit” their teeth over their heavy sorrows, and to purchase the sympathies of the chastened spirits of that tomb with offerings of immortelles and budding flowers.

How did Abelard’s dramatic life influence his theories of atonement? Next time, if the trolley car doesn't run over my stick of peppermint candy, and make it look like a lolly-pop, I’ll tell you about Abelard’s views on atonement.