I have recently come across several articles that make the argument that the reason for the decline of religion in the last two decades or so is not due to its rightward drift but because it has grown slack and essentially spineless. It no longer stands firm in defense of core beliefs but has allowed tenets of faith to become matters left to the individual. Recall the old joke about the ten commandments becoming the ten suggestions. This departure from adherence to straightforward religious doctrine has made it almost indistinguishable from the secular world. At that point, so the argument goes, why bother with religion at all?

The NY Times’ columnist Ross Douthat is one of those making this charge. With his book, Bad Religion, he argues that Christianity’s decline follows from its accommodation of modernism and its adoption of the view that beliefs and commands are optional: “A choose-your-own-Jesus mentality encourages spiritual seekers to screen out discomfiting parts of the New Testament and focus only on whichever Christ they find most congenial.” It is this trend that that drives the conservative Catholics’ concern about Pope Francis:

And they worry as well that we have seen something like his strategy attempted before, when the church’s 1970s-era emphasis on social justice, liturgical improvisation and casual-cool style had disappointing results: not a rich engagement with modern culture but a surrender to that culture’s “Me Decade” manifestations — producing tacky liturgy, ugly churches, Jonathan Livingston Seagull theology and ultimately empty pews.

And so, the implication is that, for religion to thrive, it must adhere to established rules and doctrines and remain steadfast to the conviction that, besides the one truth, there is no other truth.

On the other hand, as more fully set forth in a prior post, Republicans and Religion, I have also read about studies which suggest that religion’s identification with conservative Republican politics is the actual cause of its decline.

Once I applied myself to this quandary, it didn’t take long for me to realize that this tough anti-status quo yet non-doctrinaire approach precisely describes the preaching of Jesus. Time and time again he makes difficult, nigh on impossible demands on people – but he never requires adherence to particular rules, nor does he spell out a creed or ultimate truth that people must accept. Instead, he leaves the responsibility of figuring out things out to the individual.

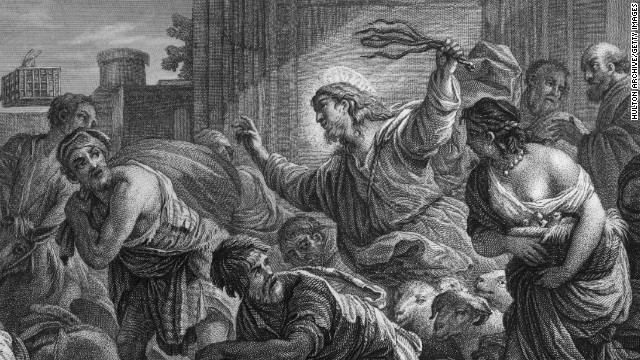

First, even though Jesus says at one point "Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets" (Matthew 5:17), its clear that he didn’t much like rules. He takes direct aim at the scribes and Pharisees by claiming, “their teachings are merely human rules.” (Matthew 15:9) He then gives the Pharisees a hard time when they criticize his disciples for picking grain in violation of the Sabbath rules, explaining to them that, "The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath.” More than once he heals on the Sabbath in violation of Jewish law. And, when he heals a man with a withered hand in a synagogue on the Sabbath, the Pharisees got so offended that they immediately “went out and plotted how they might kill Jesus.” (Matthew 12:14) And, he didn’t really care for the Jewish dietary laws, either. "Don't you see that nothing that enters a man from the outside can make him 'unclean'?” (Mark 7:18) Certainly, the notion of the law as a test for fidelity was completely foreign to Jesus.

While Jesus rejected formal rules as a basis for conduct, he did not adopt a follow-your-own-dream attitude. Instead, he replaced legalistic requirements with far more demanding and broader commands, which finally could never be completely fulfilled. Jesus makes it clear that the greatest commandment, loving God and neighbor, is without limit. He explains, “You have heard that it was said to the people long ago, ‘You shall not murder, and anyone who murders will be subject to judgment.’ But I tell you that anyone who is angry with a brother or sister will be subject to judgment.” (Matthew 5:22) Nor is this love restricted to one’s friends. You must also love your enemies (Matthew 5:43-44). And, it’s no longer an eye for an eye but one must turn the other cheek. So, if anyone sues you for your shirt, hand over your coat to him as well. (Mathew 5:38-40) Ultimately, Jesus insists that we be “perfect, even as your Father that is in heaven is perfect.”

Yet, even at his most strident, Jesus is not moralistic. Recall this rather difficult passage: “And if thy hand offend thee, cut it off: it is better for thee to enter into life maimed, than having two hands to go into hell.” (Mark 9:43) And then he says the same thing one’s foot and one’s eye. (Mark 9:45, 47) He never even hints, however, at what sort of behavior might prompt this sort of drastic action. He leaves that determination to us. But the import is clear: what you do with yourself is what counts.

And, by the way, it all must be done yesterday. For Jesus, the decision for others is an urgent one. Jesus says to one man who says he’ll follow Jesus but first needs to bury his father: “Follow me, and let the dead bury their own dead.” (Matthew 8:22) He also has no time for the person who first wants to say good-bye to his family, and tells him: “No one who puts a hand to the plow and looks back is fit for service in the kingdom of God.” (Luke 9:62)

It is thus clear that Jesus expected a lot from people and he expected it right way. You can see why people may have preferred following dietary laws.

While he wants total commitment to one’s neighbor, it’s also clear that how that commitment is carried out is up to us. And so, he criticizes those who “bind heavy burdens and grievous to be borne, and lay them on men's shoulders.” (Matthew 23:4) Indeed, the teachers of the law “shut the door of the kingdom of heaven in people’s faces.” (Matthew 23:13) They adhere to the outward observance of the law – “[y]ou give a tenth of your spices – mint, dill and cumin” – but they “have neglected the more important matters of the law – justice, mercy and faithfulness,” straining out a gnat but swallowing a camel. (Matthew 23:23-24) Any moralizing is repugnant to Jesus. "Do not judge, and you will not be judged. Do not condemn, and you will not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven.” (Luke 6:37; Matthew 7:1). “And why do you look at the speck in your brother’s eye, but do not consider the plank in your own eye?” (Matthew 7: 3)

And, lest anyone think that Jesus was pushing some kind of creed or orthodoxy, he, instead, is gleefully inconsistent. Just above I cited Jesus saying that we must be perfect as the father is perfect. But then when someone innocently enough addresses Jesus as “good teacher,” he retorts, "Why do you call me good? No one is good--except God alone.” (Luke 18:19)

And, at one point he says, “You are the light of the world. … Let your light shine before men in such a way that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father who is in heaven.” (Matthew 5: 14, 16) But later in the next chapter he says, "So when you give to the poor, do not sound a trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, so that they may be honored by men. Truly I say to you, they have their reward in full. But when you give to the poor, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your giving will be in secret; and your Father who sees what is done in secret will reward you.” (Matthew 6:2-4)

And again, at another time Jesus says, "He who is not with Me is against Me; and he who does not gather with Me scatters.” (Matthew 12:30) But then he also says, "For he who is not against us is for us.” (Mark 9:40)

Another contradiction: he states, "Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God” (Matthew 5:9) And later he says, "Put your sword back in its place, for all who draw the sword will die by the sword.” (Matthew 26:52) But then, he tells his followers, “do not suppose that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword.” (Matthew 10:34)

Perhaps Jesus would agree with Emerson that, "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds….” Or, perhaps he understood what Neils Bohr understood: “the opposite of one profound truth may very well be another profound truth.” Or, Jesus may simply prove F. Scott Fitzgerald’s point: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

One thing is clear, however: Jesus demanded a lot from people. In fact, he demanded their whole lives. But there were two things he clearly did not demand of them: that they adhere to a list of ironclad rules; and that they believe in some final truth or doctrine.

5 comments:

It's not that we haven't heard this before from you. Even your quotes are better recycled than the best conservationists. However, (to use another well used metaphor) just because the sun rises each day doesn't diminish the miracle.

Reading this, even if you disagree, is such a joy. It may even qualify for Poetry Sunday. It's not that it's different, it's that it's so well done. You're the Robert Louis Stevenson of the Jesus myth.

I thought that I started out with an original idea but as I kept getting more material, I began to realize that this post was looking awfully familiar. Oh well, Walt Whitman spent his entire life writing and re-writing Leaves of Grass.

But, the new idea I wanted to get at was how empty and ultimately silly is idea that, for religion to be real and somehow weighty, it has to be narrow-minded and rule-bound. I think Jesus pretty much dismantles that notion.

I don't consider myself a very good manager and, fortunately, I haven't had to mange many people in my day. But I know a single management principle that I have found works pretty well, and Patton of all people said it: "Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and they will surprise you with their ingenuity." Jesus apparently followed this principle. It's like he is saying, this is what I want you to do: love your neighbor, make the lives of the people around you better. But I'm not telling you how to do that. Surprise me with your ingenuity.

I really shouldn't have sounded like there weren't any new ideas here. Extremely well done, familiar, but, you're right, there are some worthwhile new ideas and nuances of old ones. Plus, it should be required reading for everyone.

In fact I have been thinking about and have written in a different venue about one of your ideas as presented in the last line—the belief in some final truth or doctrine. Whether or not it happens is still a question, but, it seems to me that we could be headed into an unprecedented part of history.

For the last 300-400 years people have confused the purposes of both science and religion. No doubt this was religion's fault more than science, but they both influenced each other. I won't drag this out but one of the repercussions is that both started thinking about one final principle. For religion this was a deistic, philosophical god; for science a god-like, final law that would reveal the truth about the universe.

For the first time, with various 20th century theologians, WWI, quantum science, and all these new talks and books on the known unknown and uncertainty, I think this 400 year trend might be reversing and, thank goodness, people will start thinking more in terms of what is more reasonable or worthy or a better course of thought or action rather than how close it is this to the final truth.

I just saw Particle Fever, a documentary that tells the story of the Large Hedron Collider's search for the Higgs particle. It's not all that concerned about teaching people quantum physics, but it tells a great story and the handful of scientists it follows are -- well- pretty entertaining.

But, based on the movie, I'm not so sure that the revolution in science that you want to announce has occurred. More than once, a scientist would make a comment like this: we've waited 30 years without an answer to the question of the existence of the Higgs particle; I just want to know the truth. As if it were some final thing. In fact, as the movie points out, the CERN experiments raised more questions then they answered.

At any rate for more information see David Kaplan's documentary 'Particle Fever' shows the human side of physics.

Higgs may be the most misunderstood particle in years. I'll include myself in that too. First of all its not a particle (mostly), its a field. The Higgs field is the important item that gives things mass. And what is a field? It's seems to be related to pixie dust. Everything is explained by fields now. (It used to be aether, but mathematically, fields are better.) A field is the consistent tendency for the universe to do something. A field, as far as I can make it, is a tautology. This is mathematically how the universe works, so let's call it a field.

Additionally, do you know how much of our mass depends on the Higgs field? Maybe 13%. The Higgs field slows down electrons and other fundamental particles (not protons and neutrons) below the speed of light so they have some mass. We already knew that electrons don't travel at the speed of light. Now we a Higgs field to 'explain' why. (Most of your mass comes from E=mc2.)

So when someone says things have mass because of the Higgs particle, they are doubly wrong.

Post a Comment